So the Darkness Shall Be the Light

Contemplative Care Comes of Age at a Symposium in Garrison, New York

By Joe Loizzo

The thing that most made my internship at a preeminent Harvard community hospital seem like a descent into what Buddhists call the hungry ghost realm was coming face to face with the limits in our modern medical approach to the natural process of aging and dying. A disturbing experience with a dying patient one night when I was on call left an indelible impression that will forever remind me of those limits.

Admitted from a nursing home earlier that day for pneumonia, the woman—whom I’ll call Mary—was quickly given antibiotics, but her blood oxygen had to be monitored to be sure she didn’t need to be put on a respirator. As the night intern, I had to draw blood from an artery in her wrist, run it on ice to the lab, and act on the result if necessary. Emaciated and hovering between sleep and coma, Mary showed few signs of recognition as I went through the prescribed steps: introducing myself, explaining the procedure, and asking for her consent and cooperation. She barely responded as I tried to soothe and prepare her by stroking her hand. I can still hear her labored breathing and feel her body squirm in safety restraints as the needle punctured her wrist. Tapping the radial artery is usually the most painful of blood tests.

When I learned that Mary had died the next day, despite her healthy blood oxygen level and her initial response to treatment, I was haunted by the image of her squinting eyes and grimacing face, as she lay in a dark and drab hospital room with a young intern who could have simply comforted her like a son but had to stick her with a needle instead.

It’s been 30 years since that night, but I found Mary on my mind one recent Saturday morning as my train left Manhattan and tracked up the Hudson River, through a rolling landscape of mist-veiled cliffs, gorges, and vistas that looked for all the world like a Zen scroll painting. From the Garrison station, a trailhead led through the woods to the Garrison Institute, a former Catholic monastery where the Manhattan-based New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care (NYZCCC) was holding its first Buddhist Contemplative Care Symposium on palliative and end-of-life care, in partnership with the Garrison Institute. By the time I’d made it up the Institute’s granite steps, I’d already been serendipitously welcomed and embraced by the dynamic duo who founded NYZCCC and were now convening the historic symposium.

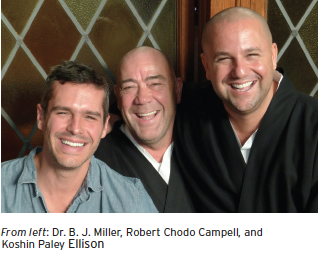

A naturally warm and outgoing pair, Robert Chodo Campbell and Koshin Paley Ellison look otherworldly in their black Zen monks’ robes and shaved heads, but they are engaged in a very down-to-earth mission: to help heal and transform our modern world’s conflicted relationship with the suffering of illness, aging, and dying. As the perfect complement to modern medicine’s all-out war on illness and death, Chodo and Koshin bring a meditative approach to the hard choices we face as we near the end of life.

Their contemplative direction works to heighten our capacity for mindful presence, acceptance, and attunement, insuring the quality of our all-important last journey in life rather than focusing on fighting the inevitable until we lack the strength of mind to say goodbye and let go with courage and gratitude.

Once the gong of the opening meditation had sounded in the stained glass-illuminated hall, the day unfolded like a cross between a spiritual retreat and an information-packed clinical conference. Most of the participants were professionals—doctors, nurses, social workers, and chaplains—working in the emerging fields of palliative care and hospice care. Their faces seemed to drink in the air of mindfulness and compassion. The questions they asked after the meditations, presentations, and panels helped explain why. Although the last decades have spawned the new fields in which these brave pioneers work, our popular consciousness and professional approach to death haven’t changed much overall. How do we bring the qualities of mindful presence to terminal illness and end-of-life care when our hospitals are still anesthetic and impersonal and our medical system still attacks illness and death with a violence that treats quality of life as an acceptable casualty of medically necessary life-or-death treatment?

Once the gong of the opening meditation had sounded in the stained glass-illuminated hall, the day unfolded like a cross between a spiritual retreat and an information-packed clinical conference. Most of the participants were professionals—doctors, nurses, social workers, and chaplains—working in the emerging fields of palliative care and hospice care. Their faces seemed to drink in the air of mindfulness and compassion. The questions they asked after the meditations, presentations, and panels helped explain why. Although the last decades have spawned the new fields in which these brave pioneers work, our popular consciousness and professional approach to death haven’t changed much overall. How do we bring the qualities of mindful presence to terminal illness and end-of-life care when our hospitals are still anesthetic and impersonal and our medical system still attacks illness and death with a violence that treats quality of life as an acceptable casualty of medically necessary life-or-death treatment?

In place of quick fixes or high-tech solutions, the conference speakers—including Chodo and Koshin, physician Diane Meier, the founder of the Center for the Advancement of Palliative Care, and other thought-leaders in the field—offered complementary healing arts and an intimate spirit of unconditional presence, as well as their long-term vision of a cultural shift toward an enlightened acceptance of death and dying. Oncologist Anthony Back led a group exercise aimed at an awareness and transformation of the deep emotions stirred up in the presence of death. Palliative care physician B. J. Miller took participants on a thought-provoking journey through the medical humanities of philosophy, poetry, art, and architecture to a vision of healing approaches, environments, and communities that would help individuals and families transform their last moments together into uplifting experiences of beauty, belonging, and meaning.

The historic gathering was an auspicious sign, marking the beginning of a new hybrid field in which health care and the contemplative arts work together to make death an ultimate good. From the standpoint of contemplative care, a good death is one that respects

the dying person’s need for dignity and intimacy, fostering a sense of the dying process as a culminating illumination of the meaning of life for both the person dying and those bearing witness. As many of us know from our own experience with dying friends or loved ones, the end of life often offers rare opportunities to affirm and deepen our highest human values—reconciling conflicts, sharing forgiveness and gratitude, deepening a sense of loving intimacy, and rising above our myopic experience of ourselves, our lives, and the world. So it is no surprise that most spiritual traditions see contemplative care as a rich vocation, offering practitioners an ideal vehicle for putting their spiritual aspirations to relieve suffering and promote human flourishing into real-world practice every day.

If taking a mindful approach to the end of life can be so beneficial, why is there still such confusion surrounding contemplative care? From a Buddhist perspective, the root of this lack of awareness lies in our modern materialist view of death. In reducing life to mindless matter—and mind to the physical brain—modern science, medicine, and popular culture have come to see death as a mere off switch, a full stop followed by nothingness. From this radical materialist view, we literally have no experience of death; therefore, the quality of our experience at the end of life just doesn’t matter. So the only human value modern materialist science can subscribe to is to prolong life at all costs, as long as possible: hence the medical emphasis on maintaining quantity over improving quality at the end of life. This bias persists despite the challenge presented by studies of people in coma states and a growing body of solid research on near-death experience indicating that many of us do indeed have vivid experiences when our bodies and brains meet the criteria to be pronounced dead. Many who come back to life after resuscitation can recall in detail events that took place in the room after they were supposedly dead, and some describe their near-death experiences as unimaginably heart- and mind-opening and permanently life-altering. While these findings are only a small part of the argument for a paradigm shift toward emphasizing the quality of the end of life, they do raise questions about the accepted science of death. In addition, growing concern about the mounting human and economic costs of our medical system’s de facto denial of death and dying seems to be moving us toward increased support for contemplative care.

Founded in 2007 and inspired by the work of the late Issan Dorsey, a Zen Buddhist monk who established the Maitri Hospice in San Francisco, the New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care has already had a rich history of successful partnerships and initiatives. It provides New York’s Beth Israel Medical Center with contemplative chaplaincy interns and has partnered with New York–Presbyterian Hospital. NYZCCC works closely with key hospice services, including the Visiting Nurse Service of New York Hospice and Hospice & Palliative Care of Westchester. It is also a national leader in education and training, offering a yearlong Foundations in Buddhist Contemplative Care, a fully accredited two- to four-year clinical chaplaincy program in Clinical Pastoral Education, and the recently launched Buddhist-track master’s program in Pastoral Care and Counseling at New York Theological

Seminary. The center is even at the forefront of bringing contemplative approaches to palliative and hospice care into medical training, thanks to an ongoing collaboration with the Arizona Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine.

Over lunch, NYZCCC’s cofounders Chodo and Koshin and their Zen teacher, Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara, underscored the practical nature of the training programs, which prepare graduates to find jobs in a fast-growing field. I had the good fortune to sit in on a meeting to plan the publication of a volume on the clinical practice of contemplative care that would distill the rich offerings of the conference for practitioners around the world who couldn’t make it. The book will be the first to bring the healing wisdom of many spiritual traditions and all clinical disciplines to the complex challenges of facing aging, illness, death, and dying with compassionate openness and artful presence.

Lest you wonder if our hardworking pioneers are as severe as their black monks’ robes might suggest, in true Zen style they surprised and delighted conference participants by inviting New York State poet laureate Marie Howe as a special guest, to recite her own poetry and an array of requests. Her presence brought to mind some lines from T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets that I wish I’d had the courage to read to my patient Mary that night 30 years ago:

I said to my soul, be still, and let the dark come upon you

Which shall be the darkness of God. As, in a theatre,

The lights are extinguished, for the scene to be changed

With a hollow rumble of wings, with a movement of darkness on darkness,

And we know that the hills and the trees, the distant panorama

And the bold imposing facade are all being rolled away—

Or as, when an underground train, in the tube, stops too long between stations

And the conversation rises and slowly fades into silence

And you see behind every face the mental emptiness deepen

Leaving only the growing terror of nothing to think about;

Or when, under ether, the mind is conscious but conscious of nothing—

I said to my soul, be still, and wait without hope

For hope would be hope for the wrong thing; wait without love,

For love would be love of the wrong thing; there is yet faith

But the faith and the love and the hope are all in the waiting.

Wait without thought, for you are not ready for thought:

So the darkness shall be the light, and the stillness the dancing.

Now I can not only wait but also begin to hope that today’s trainees in medicine, oncology, palliative care, and hospice care may meet teachers like Chodo and Koshin, who can give them the courage to face death and dying not just as professionals, but as fully present, caring fellow travelers on the great journey of life we all share.